There's a lot of silly rhetoric around technology sometimes, and at its heart I think is an essential misunderstanding about what technology does. It's not magical pixie dust you can sprinkle on problems to make them disappear, nor it is it a dangerous evil to be contained. It's simply a power multiplier.

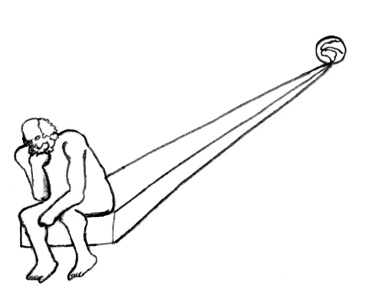

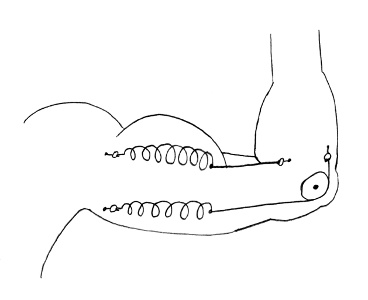

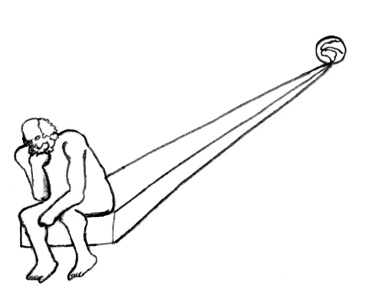

The earliest machines, so called simple machines, were things like levers and pulleys. These machines don't increase mechanical power, they just allow you to trade distance with force. Even today's machines, sophisticated as they are, still can't create energy from nothing, they can only move it around. However, by doing so they amplify a more abstract kind of power: one person can move a heavy rock with nothing but their own body and a length of wood. That person is more powerful in the sense that they have more ability to affect the world around them.

Of course, technology as a whole goes back far before simple machines, and includes wheels, fire, stone tools, and even some tools that predate humanity. What these technologies have in common is that they allow their users to do things they couldn't do before, or do them better. Every one of them allows us to use our finite energy more efficiently, or recruit other sources of energy to amplify our own. By doing so they increase our power, both collectively and individually.

Today, I can compose a piece of music on my computer, upload it to the internet, put it on an online marketplace, and (if it's good) become a successful musician. I can write my opinions somewhere and, if they're good enough, they will become popular, spread, and change the way people think. I can create software which, if it's useful enough, could be an important part of the way other people work. None of these things would be possible to do on my own if not for the enormous increase in power brought by all these forms of creative technology I have access to.

There's nothing essentially good about this, or essentially bad. If I want to help people, I can help way more people today than I could have thousands of years ago. If I want to hurt people, it's certainly possible to do that at a much larger scale than at any other time in history. It's not the technology that's causing these things, it's us. Both the best and the worst of us have become far more powerful.

It's for this reason I am somewhat nervous about the idea that technology will deliver us from our social problems. Sure, perhaps at some point we will become so powerful that we are impervious to harm. But won't the power of others to harm us increase as well? If anything, social solutions seem like they will only become more important as the people in society become more powerful and the consequences of social problems become more severe.

It's easy to dismiss electronic music if you're used to live acoustic or classical music. When you see a skilled musician on stage, you know they have spent thousands of hours learning every nuance of their instrument, practicing and refining until their bodies are, themselves, instruments. To see all that exercised in front of you is art. Electronic artists basically come on stage and press a few buttons. Where's the art in that?

Of course, electronic music fans know that the art isn't when you press the buttons. It happens much earlier, in the hours upon hours spent in production, carefully arranging and tweaking each sound in a way that is impossible when you're working in real time with ultimately fallible performers. The lack of art in performance enables the art of production.

Hip-hop has less harmonic complexity than, say, jazz or classical music. Even sophisticated hip-hop relies on relatively simple instrumentation and arrangement. In fact, most classic hip-hop is just drum loops and repetitive samples. But that's not where the art is. You have to listen to the complex percussive patterns of the beats and the vocals and the way they play off each other. That focus on the structure of the sounds rather than their tone allows for a different and powerful kind of expression it's hard to find elsewhere, with the possible exception of beat poetry.

You won't find art in comics if you're looking for life-like detail, complex brushwork, or a challenge to the limits of visual abstraction. You will find it if you're looking for extreme stylisation and larger-than-life depictions of action and emotion. You won't find art in videogames if you're looking for narrative storytelling (books do it better), character development (TV does it better) or spectacular visuals (movies do it better). The art in games is in the way they make you the storyteller, inviting you to create an experience for yourself that nobody else could give you.

And you won't find art in code by looking for animations or music or lights that blink on and off. Those things might be art, but they're animation art, musical art, or blinkenlight art. The art in code comes from exploring the nature of code itself, the way it abstracts action, the way it recursively and fractally explains itself, and the way it universally claims all computation as its own.

Art is ultimately the rendition of creativity, wherever it can be found. If something appears to be not art, perhaps it isn't, but perhaps you're looking in the wrong place. New kinds of art often look a bit like old kinds of art, so if you get too used to looking in the same place, you may find yourself falling victim to misdirection. You're trying to figure out what's going on in the magician's hand, when really the place to look was their sleeve.

In the early days of Wikipedia, there was a doctrine that every page should be available for everyone to edit, even without being logged in. In fact, the only exception was that certain IP address ranges associated with spammers or vandals would sometimes be required to sign up, but could still edit. These days, there are all sorts of other exceptions which muddies the waters a little, but at least in the beginning that was the idea.

So how did this work? I mean, how could Wikipedia possibly function when it was so easy for anyone to come along and vandalise it? Well, the trick was that the burden of vandalism and the burden of removing vandalism were vastly disproportionate. Vandals had to hit the edit button, actually modify the article, enter a change description, and hit the save button. Reverting that vandalism was just a single button, and not even necessarily on the page itself. Editors could see a live list of changes, with obvious vandalism indicators highlighted (lots of deletions, no change description, anonymous edits, popular pages) and revert them in one click. Because it was harder to ruin a page than to fix it, the system converged towards stability.

I think this is a powerful way to think about systems in general. What is easy to do in your system and what is hard? On Reddit, people upvote instead of writing "I agree", even though writing a comment would make them feel more important. Why? Because it's easier, and other people would (again, easily) downvote their boring comment. It's often tempting to assert the iron fist of system design and forbid actions you don't want people to take. However, it can be sufficient to use a soft touch and just make it more difficult to do actions you want to discourage, or make it easier to undo them.

One system where this sort of analysis is sorely needed is in popular science and the search for truth. It's very easy to say things that aren't true, and it takes a disproportionate amount of effort to argue against them. Worse still, untruth is often more compelling than boring and simple truth. The burden of fighting untruth is quite heavy, and so untruth tends to spread, the same way Wikipedia vandalism would spread if you could vandalise with a single button, but could only revert with a more complex series of actions.

This is why skepticism is so important. It might seem nicer to default to accepting things you hear, but by doing so you build a system with a greater burden for truth than untruth. On the other hand, if you assume a statement isn't meaningful until you've seen evidence for it, that burden is reversed: it's hard work to produce a false statement that can pass that bar, but easy to produce a true one. A skeptical mindset converges towards truth, and is a powerful defence against the intellectual vandlism of easy and compelling untruths.