There are some things that you think about because they're useful or interesting, because of their consequences or because the outcome of understanding them would be useful. There are things you think about because exploring the ideas brings you some degree of joy or delight. Then there are the things that you think about because you just can't seem to stop thinking about them.

This latter category seems to take up a vastly disproportionate amount of thinking time for its value. I'm talking about the internet outrage of the day, whoever said whatever inflammatory thing (oh that's so that person though), warmed-over debates in politics, philosophy or religion, and problems that it's far easier to have an opinion about than to think through properly.

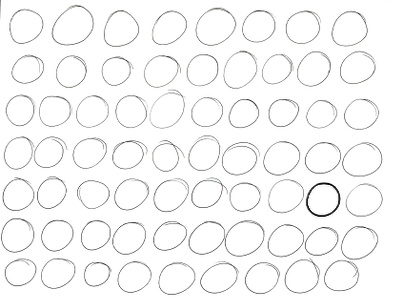

For some reason, certain topics just seem to compel thinking, whether or not it's useful or even fun thinking. Parkinson had his law of triviality, later known as bikeshedding, observing that trivial things like bike shed colours get more attention because it's easier to have opinions about them. Randall Monroe described nerd sniping, where you can pose a tantalising problem to a nerd, who will get so carried away with it they lose their survival instincts.

In the former case, thinking about the bike shed colour is a total waste of time. In the latter, it is actually an interesting problem, but probably the more interesting problem at the time is how to cross the road safely. So it's not a binary thing of either useful or useless thinking, more that there's some degree of value an idea has, and then some degree of compulsion it generates. In both cases the compulsion outweighs the value.

In news, we recognised a similar problem: headlines convey some amount of information, and have some degree of compulsion. Over time the compulsion rose out of proportion to the information, and we ended up with clickbait. In a similar vein, I think of these disproportionatly compulsive ideas as thinkbait. And, like clickbait, I think they're worth avoiding.

I recently learned about the truly ludicrous number of jazz/lounge background music videos on YouTube. I've always liked listening to music when I work, though normally more electronic than jazz. The interesting thing about jazz, though, is that it's much better suited to live performance and improvisation. Which gives me an idea...

If you got a group of performers together, you could make a live concert designed for people at work. You'd probably want to run it for 12 hours (say, 9am US East to 6pm US West), which means you'd probably need a bunch of musicians working in shifts. The whole thing would be livestreamed, but designed to be left in a background tab or streamed audio-only. Essentially you'd be trying to replicate the kind of cafe jazz experience, but combining everyone's workplaces into one giant cafe.

With the goal of staying somewhat in the background, it would rule out some of the more adventurous or experimental ends of the jazz spectrum, but I still think there'd be room for creativity as a kind of daytime equivalent to Max Richter's Sleep. For the listener, it would probably be a better musical experience than the pre-recorded videos, and there would be an interesting kind of connection to everyone else listening and working live.

I general, I feel like there are way more opportunities to use technology creatively than are really being explored at present, and internet-scale live performance is one of the easiest to get started with since the tech part is already quite mature and there's a lot of low-hanging fruit.

There was an old PVP comic I quite liked, where the caffeine-addicted Brent decides to give up coffee, but when the magazine is in crisis and the chips are down, he has to put it all on the line to save the day. He grits his teeth, takes one massive dose of caffeine... and ends up in hospital.

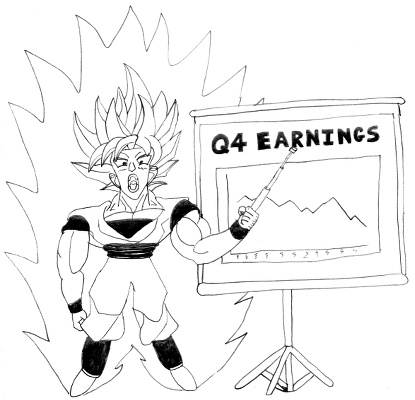

What's great about it is that it drives straight to the heart of the myth of the power move. Sure, it seems ridiculous that you could save up your caffeine intake and use it all at once, but there are lots of less ridiculous-seeming examples. It's fairly common in games and action movies to have charge-up attacks, where you, I don't know... power up your fists by getting really angry? Other times there's some harmless-looking person who turns out to have some secret talent they were just waiting for the right moment to use.

Maybe that's fine as a literary technique or a game mechanic, but the problems come when people start acting like that in real life. I'm going to learn music in secret so that the first time I play everyone will be amazed at how good I am. I'm going to develop my startup in secret so that when I go public, everyone's going to be blown away by how great it is. I'm going to avoid implementing my ideas, because I know that when I finally do something about them they're going to be a million times better for having charged up in my head.

The power move relies on a fundamentally backwards idea of where achievement comes from. In real life, you get better at something by doing it more, not by doing it less. And you have more chances to succeed the more often you do it. If you end up as a famous musician, it's pretty likely that you spent years and years making and releasing music, slowly building your skills and audience and then achieving a breakaway hit. Far less likely that after years of thinking about it, you finally record something and it turns out to be amazing on your first try. Though I admit that would be impressive.

In a sense, that impressiveness is really the problem. The power move is a fantasy. It would look so cool if you could charge up all your potential and release it in one massive burst of achievement. None of this boring incrementalism, none of this long journey through mediocrity before you get good. You just stand up and are amazing on the first try. How intoxicating! Like all fantasy, it persists because we wish it were true, not because it is true.

Of course, maybe, just maybe, you're that one in a million, and that's a hard thing to give up. But once you do it's quite liberating. No more hiding from the possibility that you give it your best, and your best turns out to be mediocre. It will be. But your best gets better with every mediocre attempt, and you'll soon surpass everyone else who's still waiting for their power move to charge.

Within the fairly obscure subculture of speedrunning, that is, trying to complete a game in the fastest possible time, there is an even more obscure sub-subculture of tool-assisted speedrunning. In a TAS, the goal is to produce, by any means necessary, a sequence of inputs that completes the game in the fastest time. These inputs often exploit frame-precise timings and bugs, and are usually recorded by a person in super-slow motion or programmed directly using code. That can lead to some, uh, fairly chaotic gameplay.

The interesting thing, though, is that no matter how bizarre and inhuman this input sequence is, there's no reason it couldn't be generated by a person, if that person was a superhuman who never made any mistakes. In fact, there are robot controllers that plug into a game console and replay a given TAS. It's interesting to consider that just recording and replaying might be the only tool you need; if you could perform even one tiny section of a TAS in real time, you could record that input, and with enough reloads and retries eventually build a perfect run entirely out of human input.

Most games already have a concept of loading and saving, or restarting the section you're on when you lose. From your perspective as a player it might take five or ten tries to get past a level, which is not that impressive. However, the game world is reset every time you fail, and from its perspective you just breeze through it in one perfect run. In a sense, all games are tool-assisted depending on which timeline you observe. Some games make it more explicit by including time travel mechanics, but really time travel is a feature of any game where you can load and save.

This concept of which timeline you observe, which attempts you get to see and which ones you don't, is quite powerful. Powerful enough to build a human-powered TAS, if you have enough patience. Powerful enough that almost all games use it to present you with problems that you can't solve on your own, but can solve with a time machine and enough attempts. And powerful enough that we use it in our everyday lives to present an impression of ability far higher than we naturally possess.

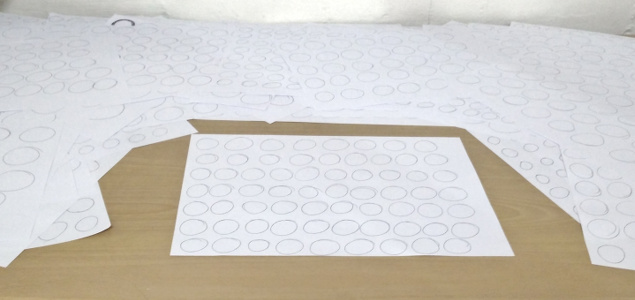

In a film, actors perform hundreds of takes that are not used, but we don't get to see them; we only see the final version, with one timeline stitched together from all the best runs. We take fifteen photos and only post the best one, leaving no trace of the other fourteen failed timelines. As I write this, I am repeatedly creating and deleting sentences, rewording and editing. When it's posted, you will only read the parts that made the cut, a representation of what I could write if I did everything perfectly the first time. But I didn't.

Of course, doing things this way genuinely does lead to a better result. We'd rather see the one amazing performance out of a hundred, or one good photo out of fifteen. But in this there's a kind of deception, because we can't ever really live up to the examples we see. The timelines of others might be flexible, but our own is fixed. When you create something, you have to endure every tiny mistake, every false start and misstep. When it's finally done, others will only see the successes, but you'll remember the failures.

For this reason, live performance has a kind of humanity and honesty that's hard to find anywhere else. An actor on a stage might have practiced more than you, or be more skilled than you, but they are on the same timeline. Everything that they are doing, you could be doing. And when they slip up, you feel a connection to your own mistakes, your own winding and imperfect path. They're not better than you, they're just you with better lighting.

But for those of us not in live performance, there is a risk that what we make ends up lacking that connection, forsaking that sense of truth in exchange for polish and a dream of perfection. One audio log near the end of The Witness makes the point that it can be worth putting traces of the process back into the work, to avoid putting up a false front by appearing to never make mistakes. I think we owe it to those who come after us to leave a bit of our humanity in the work, to leave those imperfect timelines unpruned.

I tried something like this in an earlier post on writing and editing, where you can hit replay and watch me write it in real time. I felt nervous writing that, knowing that there was no hiding my missteps. Strange, given how much I value seeing the process behind the work of others, but when you get used to polishing away your mistakes it can be hard to stop.

I don't think seeing how something was made decreases its value, and I think we'd be better off seeing it more often. For better or worse, we aren't machines, and we can't generate a flawless series of inputs every time. Sure, it might be scarier to let people see your imperfections, but why hide them when all it does is deceive others? Why pretend to be perfect by omission?