Burden

In the early days of Wikipedia, there was a doctrine that every page should be available for everyone to edit, even without being logged in. In fact, the only exception was that certain IP address ranges associated with spammers or vandals would sometimes be required to sign up, but could still edit. These days, there are all sorts of other exceptions which muddies the waters a little, but at least in the beginning that was the idea.

So how did this work? I mean, how could Wikipedia possibly function when it was so easy for anyone to come along and vandalise it? Well, the trick was that the burden of vandalism and the burden of removing vandalism were vastly disproportionate. Vandals had to hit the edit button, actually modify the article, enter a change description, and hit the save button. Reverting that vandalism was just a single button, and not even necessarily on the page itself. Editors could see a live list of changes, with obvious vandalism indicators highlighted (lots of deletions, no change description, anonymous edits, popular pages) and revert them in one click. Because it was harder to ruin a page than to fix it, the system converged towards stability.

I think this is a powerful way to think about systems in general. What is easy to do in your system and what is hard? On Reddit, people upvote instead of writing "I agree", even though writing a comment would make them feel more important. Why? Because it's easier, and other people would (again, easily) downvote their boring comment. It's often tempting to assert the iron fist of system design and forbid actions you don't want people to take. However, it can be sufficient to use a soft touch and just make it more difficult to do actions you want to discourage, or make it easier to undo them.

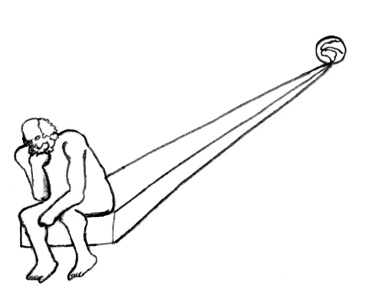

One system where this sort of analysis is sorely needed is in popular science and the search for truth. It's very easy to say things that aren't true, and it takes a disproportionate amount of effort to argue against them. Worse still, untruth is often more compelling than boring and simple truth. The burden of fighting untruth is quite heavy, and so untruth tends to spread, the same way Wikipedia vandalism would spread if you could vandalise with a single button, but could only revert with a more complex series of actions.

This is why skepticism is so important. It might seem nicer to default to accepting things you hear, but by doing so you build a system with a greater burden for truth than untruth. On the other hand, if you assume a statement isn't meaningful until you've seen evidence for it, that burden is reversed: it's hard work to produce a false statement that can pass that bar, but easy to produce a true one. A skeptical mindset converges towards truth, and is a powerful defence against the intellectual vandlism of easy and compelling untruths.