I've been working on a little Javascript utility library called Catenary for the last couple of weeks. It's based on the concatenative (aka stack-based) paradigm, and particularly inspired by the Factor language. It initially just started as me noodling around writing some Factor primitives in JS, but it's turned out to be a lot more fun than I expected.

It's still not ready for the real world yet, but while working on it today I had one of those "a-ha!" moments. I think they're the most satisfying thing you can really experience while working on an idea. You stumble around in the dark working off nothing but feel, completely lost. But, slowly you piece together shapes. Certain movements start to seem familiar. Suddenly, something clicks. This part is the same as that part. In fact, maybe they're all the same part. A-ha!

With catenary, you can write things like this (final syntax pending):

coffee> cat(2, 3, 4)

{ _stack: [ 2, 3, 4 ] }

coffee> cat(2, 3, 4).plus

{ _stack: [ 2, 7 ] }

coffee> cat(2, 3, 4).plus.times

{ _stack: [ 14 ] }

Basically, we use property access to perform operations on a data stack. As well as performing operations on the stack, you can get data into and out of the stack using the special functions .cat and .$, like this:

coffee> cat(1, 2).cat(3)

{ _stack: [ 1, 2, 3 ] }

coffee> cat(1, 2).cat(3).plus

{ _stack: [ 1, 5 ] }

coffee> cat(1, 2).cat(3).plus.plus

{ _stack: [ 6 ] }

coffee> cat(1, 2).cat(3).plus.plus.$

6

So that's fun, but when you want to do anything higher-order you need a way to create those function chains without executing them immediately. For that, you can use a function-building style, which allows you to build up a Javascript-friendly function whose arguments become values on the stack, like this:

coffee> cat.plus

{ [Function] _funstack: [ [Function] ] }

coffee> cat.plus(3, 4)

7

coffee> cat.plus.times

{ [Function] _funstack: [ [Function], [Function] ] }

coffee> cat.plus.times(2, 3, 4)

14

The way it works is actually fairly simple, the function stack (aka _funstack) is built up with every property you access. When you're ready to call your function, it initialises an empty data stack and calls all of the funs in the funstack in order.

My particular a-ha came today when I was trying to sort out how to do flow control. To call a function, on the stack, you do this:

coffee> cat(1, 2, cat.plus).exec

{ _stack: [ 3 ] }

Which can be pretty awkward, especially if you want to chain a lot of function calls together. So I started working on the idea of a cat.fun operator which would allow you to enter function-building style at any time. That is, you could refactor the above into this:

coffee> cat(1, 2).fun.exec(cat.plus)

{ _stack: [ 3 ] }

Under the hood, cat.fun works exactly the same as our original function-building style. It creates an internal funstack with cat.exec in it, which is then invoked when you call the returned function. The only difference is that instead of starting with an empty data stack, you use the one you had when cat.fun is called ([1, 2]). Another way to think about it is that cat.fun is a placeholder that gets filled in later with the argument (cat.plus) when the function is called.

So what's the a-ha? Well, if you remember cat.cat from before, it adds things to the stack after the stack is created, so cat(1,2,3) is equivalent to cat(1).cat(2).cat(3). And that's the exact same thing as cat.fun! It just adds things to the funstack as well as the data stack.

Which means all three of these are the same:

coffee> cat(1, 2, 3)

{ _stack: [ 1, 2, 3 ] }

coffee> cat(1, 2).cat(3)

{ _stack: [ 1, 2, 3 ] }

coffee> cat(1, 2).fun(3)

{ _stack: [ 1, 2, 3 ] }

In that last example, cat.fun adds 3 to the stack, then calls its (empty) funstack.

That led to the realisataion that there might be no need for a separate idea of function-building style and regular style at all. Every catenary can have a data stack and a funstack, and that means a much more elegant system.

In fact, I've had this vague uneasy feeling about data stacks and function stacks for a while. I keep catching glimpses of something that might mean I could drop the distinction entirely and just have one single glorious omnistack.

That's at least one more a-ha away though.

I've been thinking about Bret Victor's video on The Humane Representation of Thought, and his earlier Rant on the Future of Interaction Design. Summarising intensely: we use representations (like graphs) so we can go from a domain that doesn't suit us (like reams of numbers) to domains that do suit us (like our highly optimised visual system). But Bret's point is we only use a very limited set of those domains. Most of what computers do is strictly visual and occasionally aural, with no tactile or kinaesthetic component: "Pictures Under Glass". In the transition from static tools like hammers to dynamic tools like computers, we've lost most of our sensory range.

Bret's direction is towards physical computer systems, or dynamic "smart" matter. That sounds hard, so I'm going to leave that to him. Good luck, buddy! In the mean-time, there's nothing stopping us from trying to exploit these extra underused sensory dimensions today. After all, the graph was invented long before Excel. So before Smart Matter, we can think about some ways to use more Dumb Matter to get a few more axes into our models, or arrive at insights that come more easily with when you have something you can grab and move around.

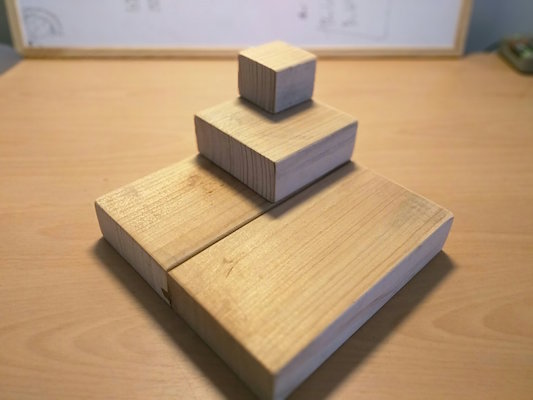

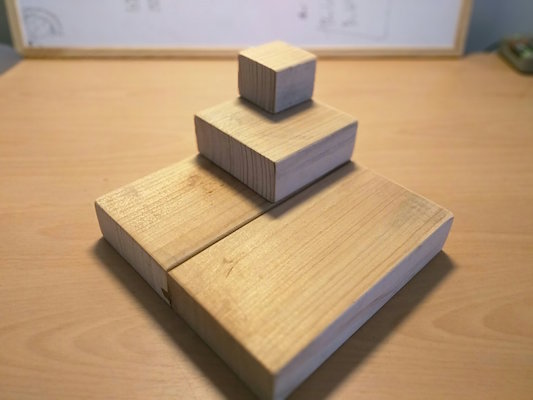

I decided to try a more humane equivalent of the classic to-do list, which I have creatively named to-do blocks. My foray into Humane Representations looked like spending an hour and a half in my shed with some scavenged bed slats and a circular saw. In the end, I walked away with a downy coat of sawdust and 14 blocks of wood: 2xlarge, 4xmedium and 8xsmall. Each size is 4x the next, so you can build larger blocks out of smaller ones.

Each block represents a task, so I write the task's name on it in pencil. I'm currently only using it for meaningful tasks ("take out the garbage" doesn't make the cut), and only things that I'm actually working on (sorry, Great American Novel). The goal is to have a physical representation of "my plate" that gives me a good physical intuition for the tasks and projects I'm doing.

I've already found a bunch of interesting ways to represent and manipulate my tasks that would be hard or impossible on paper:

- Occlusion

- You can cover one task with another task if it has to be done first.

- Arrangement

- Tasks that are close to each other are related, I've been putting things I want to work on less further away, but also roughly arranging left-to-right by due date.

- Weight and size

- Bigger tasks get bigger blocks, you can stack smaller blocks on top of bigger blocks for subtasks. The biggest blocks are actually kind of unwieldy, which I think is a good fit.

- Texture and colour

- I'm not currently doing this, but I could paint or coat blocks in something to distinguish different categories like work/personal.

- Separation

- The blocks live on a separate desk at the moment, but I take the block I'm working on and put it next to my keyboard to remind me what I'm meant to be doing. I have the "website" one here right now.

- Spatial awareness

- I can easily tell how many things I'm doing, the average size of those things, how related or unrelated my tasks are, and so on. Temporarily rearranging blocks (eg, making a stack of things to do today) works well because I can easily remember where they went before.

- Play

- It's really fun to mess around with the blocks, so it doesn't feel like a chore to keep track of my to-dos. If I can't decide what to work on, I juggle blocks until I drop one. You're it!

I'm amazed how many interesting ways to make use of the extra information have come up without really trying that hard. But beyond any of that, it's surprising just how much better it feels to be doing something with my hands, to feel shape and texture, and operate in 3d space for a change. Even if what I'm doing turns out to be no more useful than a regular to-do list, I'd be happy to keep it for the humane-factor alone.

What I'm wondering is, what else could you use blocks for?

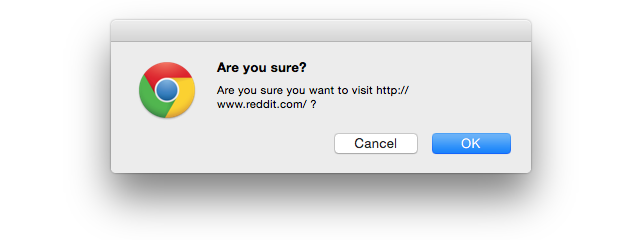

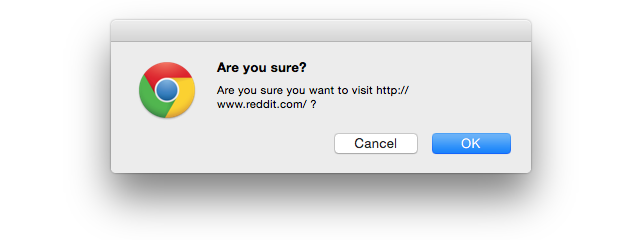

Today I'm releasing Are you sure?, a little Chrome extension that prompts you before you visit certain websites. I often get distracted by Reddit or Hacker news when I'm meant to be doing something useful, and this is my own particular take on that problem.

I think that in many cases we overreact to mild cognitive flaws and biases, unreasonably punishing our monkey brains that are already trying as hard as they can to keep up. While I respect the power and depth of extensions like StayFocusd, I can't help but feel that strict schedules, time limits, and having to write lines on a virtual blackboard to use your computer is more masochism than self-improvement.

For my needs, I mainly trust myself. If I really want to, there are a hundred ways I can get around a website blocker. And sometimes I really do need to visit Hacker News or Reddit for work. I don't need a strict taskmaster, I need a helpful friend; someone to ask "hey, man, is this really what you want to be doing?". Are you sure? is an extension from that school. It only prompts you once, just enough to interrupt your muscle memory and ask you to actively make a decision about whether to waste time or not.

After that, it's up to you.