It strikes me that in a very real sense we are slaves to our biology. What I mean by this is that because our bodies require a constant input of resources for maintenance, we are indebted to that requirement. This puts us in a kind of debt bondage: we have to work to pay off that biological debt, and the penalty for non-payment is death.

For that reason, the notion of wage slavery seems short-sighted to me; it's not wages that are responsible, it's our biological needs that give power to those wages. If some freak of genetics caused you to be biologically self-sufficient - powered by the sun or some such - you would have no particular need to work. The idea of wage slavery under those circumstances would seem very far-fetched.

Indeed, if you earn enough money you can reach a point where you have enough to cover your body's needs for the rest of your life. I would say that at that point you have purchased your biological freedom. Though obviously some people don't earn enough to do that until very late in life, and some people inherit resources enough to be born free.

To accept this view is to accept the notion of biology as unfair. Why should we be born into a world with this debt attached to us? Wouldn't it be more just if we could start with a blank slate? And indeed to some extent many countries accept this in the particular subset of medical needs. We acknowledge the unfairness that some people are born with or acquire expensive medical problems that drastically increase their biological debt, and we pay to free them of that debt.

But you have to ask, isn't anything that causes you to get sick and die a medical problem, even if it affects everyone? And shouldn't it be a priority for us as a species to remove that burden?

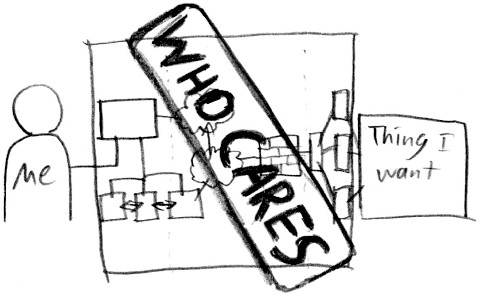

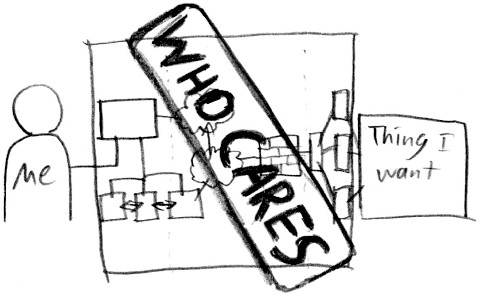

Something I've noticed is that as technology begins to mature, the particular internal details become less important. As the technology becomes sufficiently advanced, it becomes completely invisible. At that point, we don't feel like we're interacting with technology. Rather, we're working with its consequences directly. In other words, technology makes the transition from how to what.

Software is still very early on that journey, but there are a few places where that transition has begun. Dropbox is an early example whose success is, I think, fairly misunderstood. Dropbox doesn't succeed because it's simple, but because it's invisible. You just use your files like normal and they appear everywhere. How? Doesn't matter. You only have to think about the what: your files.

On the other hand, the technology for connecting with people is nightmarishly how-centric. The blame for this mostly lies at the feet of the dominant user-capture strategy in social startups, but the number of different ways you can send a message, share a picture, post an update or make a call is completely dumbfounding. The most damning result of this is Android's Share menu, a giant grid of "how" options that comes up before you even get to pick who you want to share with.

I think the first technology to make all of that invisible and let you just focus on the people, rather than how you talk to them, will do very well for itself.

I've been pretty busy the last two weeks, and I think my creativity has suffered as a result. Being busy sounds very productive, but on reflection I think it is a signal that your time is being badly managed. The feeling of busy-ness is a feeling of stress, a kind of animal urgency. It stops you from seeing beyond your immediate situation and engaging your higher-level thinking. I think if you want to be creative you need to cultivate the opposite of busy-ness: space.

Space is that feeling when you aren't reading, watching or catching up, not doing or going or working. Space is when the external fades away and you're left alone with your thoughts, to wander where they lead and explore with the freedom of a child. It's very easy, and very tempting, to fill every second with stuff, but if you can make time for space I think you'll start to hear some quiet voices that were drowned out by the noise.

I think I'm going to start going for more walks.

Quick update on Chia Groot. He's been growing for a week now and looking amazing.

A topic came up in conversation today that I think is really important: what's so special about computers? It's often said that software is eating the world, meaning that every business, every process, every aspect of our lives seems to involve computers in some way. We talk to friends on computers, spend money with computers, and the few places where computers aren't being used much are just waiting targets for software businesses. Indeed, it seems like the dominant startup model at the moment is find an industry where they don't use enough computers and make them use more.

Okay, but why couldn't medicine be eating the world? Or insurance? Or internal combustion engines? What's so special about computers? Well, I think the best way to answer that is to look at another world-eating invention: currency. Trading existed before currency through barter and gifting, but the idea of currency fundamentally changed trading because it acted as an abstract unit of value. You don't have to trade a bushel of corn for a bunch of bananas, you trade a bushel of corn for 20 units of value, which you can turn back into a bunch of bananas.

In practice, that doesn't sound particularly special: you're still trading corn for bananas. But having an abstract unit of value involved gives rise to all the other possibilities of the modern economy. Savings, loans, interest, insurance, investment, taxation - all of these things wouldn't work well or at all without it. The reason why currency is special is because it created that abstract unit that let us connect everything else together. Of course, currency itself is based on an even more important abstraction: numbers, an abstract unit of information.

Computers create a similar abstract unit, but a much more powerful one: an abstract unit of operation. That is to say, anything that can be done can be done by a computer (with only a few fairly obscure exceptions). Of course, to begin with most of those things are pretty mundane. I could write a document already, now I type into a computer and the computer writes the document. But, in exactly the same way, having that abstract unit of operation has transformed everything we do, and will keep transforming it into the future.

So while it might be tempting to think there'll be a next big thing and computers will stop being such a big deal, it just isn't possible. They may change shape or be made from different things, but the abstract unit they embody will never stop being relevant. Computers are special because they are the abstraction of doing things, and there will always be things to do.