There's something incredibly compelling about big conspiracy theories. Secret groups of well-connected people running the world like a shadow government, tentacles reaching into every boardroom, every cabinet meeting... that sort of thing. Of course, there's no evidence for any grand-scale conspiracy and, although there are examples of small scale conspiracies here and there, even those are pretty rare. But maybe the issue is that conspiracy-hunters are looking for the wrong thing.

Inherent in the idea of a conspiracy is an agreement between people, something explicit and human-powered. But if the past century has taught us anything, it's the incredible power of systemised and automated processes, with as few people involved as possible. Surely a conspiracy that could be effective on a global scale would have to be very different from what we'd imagine. It wouldn't be run by people, but by processes. A kind of automatic conspiracy.

Let's imagine some nefarious secret organisation wants to keep people stuck docilely wasting time on their computers all day for some Evil Purpose. The conspiracy would set about researching ways to make computers addictive, give them features reminiscent of slot machines, and carefully optimise every facet of their operation to maximise those compulsive qualities. A spooky theory to share with your fellow conspiracy buffs! But of course it is actually happening, and the only part that isn't true is that there is some secret cabal driving the process.

Instead, it's just a series of fairly straightforward incentives. People value free things irrationally highly, so it's a good idea to make your money from advertising or microtransactions instead. Both of those work better the more you get your users to engage with your product. And, of course, you're competing with all the other products to do this most effectively. The modern analytics-driven software world lets you experiment on your users and optimise every decision to maximise engagement. If that engagement happens to look a lot like addiction, well, I guess our users just really like us.

If a group of people were driving this process, we would of course ask them to justify its ethics. But there is no group. If there's a puppetmaster pulling the strings it's none other than our old friend the invisible hand: each person acting individually is acting collectively, as long as the incentives are aligned. And because what we see doesn't look purposeful, we don't question its purpose.

But the systems that we have built give rise to far greater conspiracies than we could dream of hatching with mere humans in a darkened room.

I was trying to organise coffee with a friend today and it was pretty irritating going back and forth about times. It's a problem that's come up a lot recently and I'm getting dangerously close to the point where I start making something to solve it.

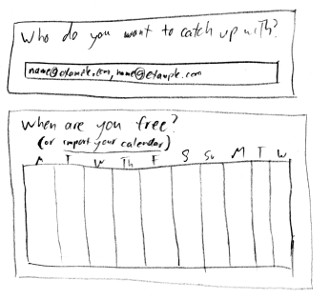

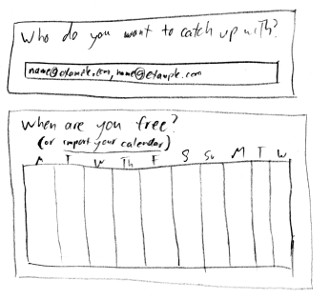

So here's my first sketch for how it might look. Basically you enter emails of the people you want to catch up with. Then you get a calendar widget to choose what times to suggest. You can import your calendar to speed up the process, and if the other invitees are already in the system their calendars are overlayed as well so you can narrow down the times even more.

Then it generates some standard language like "I'm free all day Tuesday, Wed 3-5pm, Thurs 9am-1pm & 3-5pm. You can check out my full calendar here: http://site.com/link". When someone clicks the link they can narrow it down to their own availabilities. The point is that it interoperates well by allowing you to keep the discussion happening through email by default, but with the website augmenting the process so it should ideally only take one round trip.

I haven't made any particular steps towards this yet, but give it a few more catchup discussions and I'll probably get cranky enough to do it.

This is aquire, a little node library I've been working on to do asynchronous node module downloading and importing. Whereas previously you'd have to do this:

$ npm install coffee-script@1.7.0

And then this:

coffee = require('coffee-script')

eval(coffee.compile("(-> console.log 'hello, world!')()"))

With aquire you can do it all in one step:

aquire = require('./aquire')

aquire('coffee-script@1.7.0')

.then(function(coffee) {

eval(coffee.compile("(-> console.log 'hello, world!')()"))

})

It invokes npm, installs the module and all its dependencies for you at run time, and then resolves the promise when everything's ready. Modules are cached in a specific aquire_modules directory so only the first time should be slow.

There are still a few bits to work out, like how to deal with multiple different versions being required simultaneously. I also want to add client-side js support. But for now at least I think it's an interesting take on the various module loading systems.

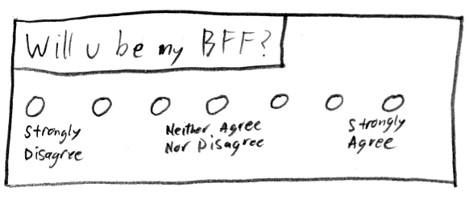

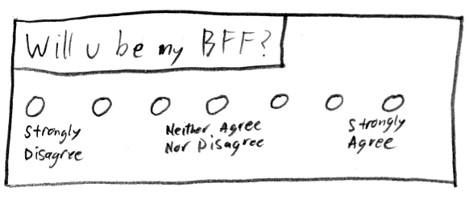

A friend recently asked me to fill out an anonymous survey for a CFAR workshop he was doing. It contained all sorts of questions about how effective the person was, whether they responded well to criticism and contrary information, whether they think clearly and help solve problems etc. I found the whole thing quite confronting, but in that good discomfort sort of way. How often do your friends tell you your strengths and weaknesses?

It occurs to me that we recognise this problem – the essential conflict between politeness and useful feedback – in the workplace, and we use performance reviews to overcome it. The particular structure changes from company to company, but the core idea is the same: set aside a specific place and time for feedback to break that social barrier. So why not do the same in personal relationships? I admit it gives me the heebie jeebies a bit, but it could be a pretty productive way to find problems or issues that are obvious to your friends but not to you.

Or maybe you'd find out you have no flaws, which would be okay too.

Something I've noticed is my tendency to over-focus on getting something done. I've often spent a long time working on something in private with the goal of getting it to the done stage: a point where I'd be happy to put it out in public and let the world have at it. I've previously noted that this leads to long feedback loops and performance anxiety. In addition, waiting until something is done can take an unnecessarily long amount of time, and deprives other people of the opportunity to judge for themselves whether what you're doing is good enough for them.

Those are all problems on the way to done, but the biggest one is on the other side: what next? Sometimes you may have the benefit of a project that you throw over the wall and never have to touch again, but usually getting it done is just the beginning. To get people to care about a project is a whole new task that really has very little to do with how done it is. And what if you're not as oracular as you imagined, and your beautiful done thing actually still needs some work? Are you going to do that work if, to you, it is the essence of completeness?

So I am learning to be happier with projects that aren't done. In that spirit, here is something I have been sitting on for way too long: Robot Party. It is a kind of mash-up of actor-model programming and IRC, with the goal of making a kind of virtual space where people and code can both exist as tangible things. The gory details are in the code, but I'll do a better writeup later.

You're welcome to get in contact if it's something you'd be interested in getting involved with. It's definitely not done, but perhaps it's done enough.