I was recently thinking about my friend Jeremy's On struggling, about whether difficult things are actually better than easy things. Of course, it's important to challenge yourself sometimes, but should it always be a struggle?

One of my fondest experiences at university was when I did the catering for a student theatre show during their production week. I'd done various things in and around student theatre, up to and including directing a show myself, but I don't think there was any experience quite as good as organising the food. The other things I did were pushing myself, expanding my limits by trying something I wasn't sure I could do. This was the opposite. It was so firmly within my capabilities that I had no doubt I could do it well. And I did a great job at it. It was easy.

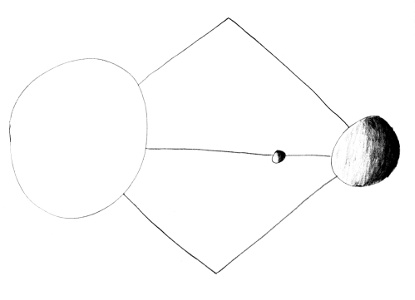

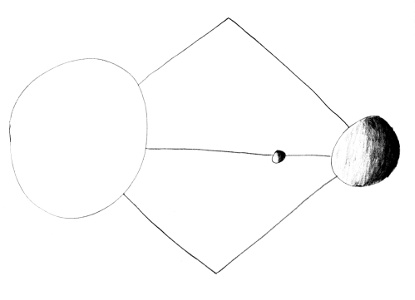

I think there is something unique and amazing about that feeling, the exercise of competence. The virtuous struggle is one thing, but when you do something that you are truly good at, it just feels right. Like a screwdriver is to a screw, a hammer is to a nail, you are to your task. You were made for this. It is beautiful to exercise yourself in this way, and it only comes by not challenging yourself.

I'm reminded of a section from Venkatesh Rao's The Calculus of Grit called Hard Equals Wrong: "if you find that what you are doing is ridiculously hard for you, it is the wrong thing for you to be doing". Maybe this feeling of ease, far from being an indication that you're not trying hard enough, is an indication that you are doing the right thing. It's hard to use a wrench as a hammer, but that doesn't make it virtuous, it just makes it wrong.

And yet we're not hammers, wrenches or screwdrivers. We have the gift and curse of being a tool that can do anything; the marble and the sculptor. I still remember being a teenager and struggling – really struggling – to understand structs in C. Today I don't remember why it was difficult, can't even imagine why it was difficult, I just have the memory of suddenly realising how much I didn't understand. I wondered if I would ever understand, or if perhaps I had reached the limits of my intelligence. It was hard.

So I can't help but wonder, what if I had found it too hard and stopped? The only reason programming is easy for me today is because it was hard back then. I didn't always struggle, by any means, but there were more than enough times where I felt like my brain was too small to fit what I was trying to learn. Each time I encounter something where I don't have an existing comfortable base of knowledge, from structs to EEG signal processing, a part of that same feeling comes back again. It's a struggle, but the struggle is what allows me to stop struggling.

Which means that easy and hard are both necessary. Or, more accurately, to exercise your skill you need both skill and exercise. The skill comes from the hard but necessary process of refining yourself. The exercise is taking all that potential energy and letting it out, which feels natural and easy. Avoiding difficulty is counterproductive, but so is seeking it out for its own sake. Worse still is falling into the trap of assuming that the hard part counts for something on its own.

The hard part exists so that you can become the kind of person who does hard things easily. And that only matters if you do the easy things.

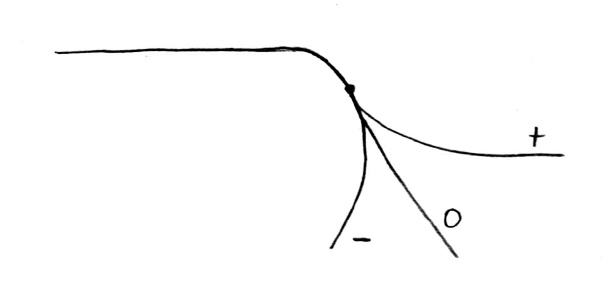

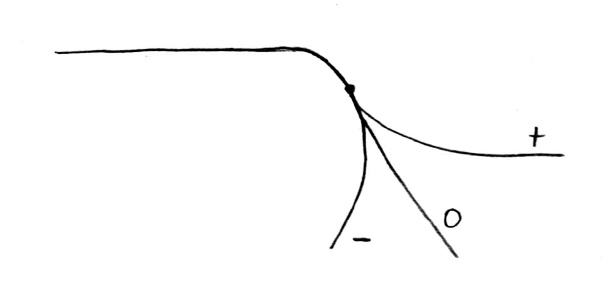

In vehicle design, it's common to talk about positive and negative stability. Positive stability is the tendency of the vehicle to return to a neutral state when disturbed. In most aircraft, if you point the nose up, the forces on the wings and tail will push it back down. Push it down and it will try to come back up. A car's steering generally has the same quality: when you turn the steering wheel, the car will try to turn back. If you let go, it will return to neutral. If it doesn't do that, it probably needs to be serviced.

I think it's important to think about your own systems in this way too. If the way you do something gets harder to control the more it goes off track, you've got a system with negative stability, and that can be very dangerous. In a sense, my description of atonement is an example of a negatively stable system. If you fail, having to atone for your previous mistakes as well as continuing to not fail is more work than just not failing on its own. That means the more you fail, the harder it gets to stop failing.

The worst case of this is when you miss a deadline and push out the deadline. In isolation this is fine, you had time T to do task X, now you have time T+n to do task X. In reality, unless this is the last task you ever do, you had time T1 to do task X and T2 for the next task Y. Now you still have the same total time, but with n units moved from T2 to T1. If your assessment for T2 was accurate, you now don't have enough time for task Y. Time to pull some more units from T3... The system gets more unstable the longer this goes on, even though the decision makes sense locally.

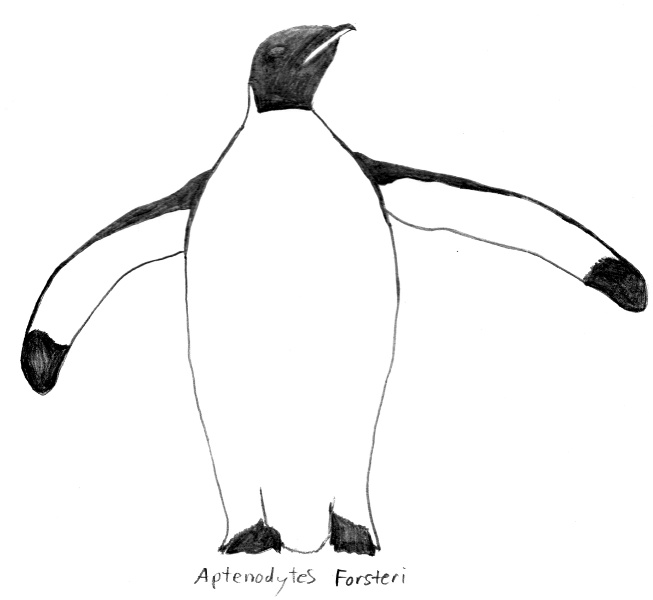

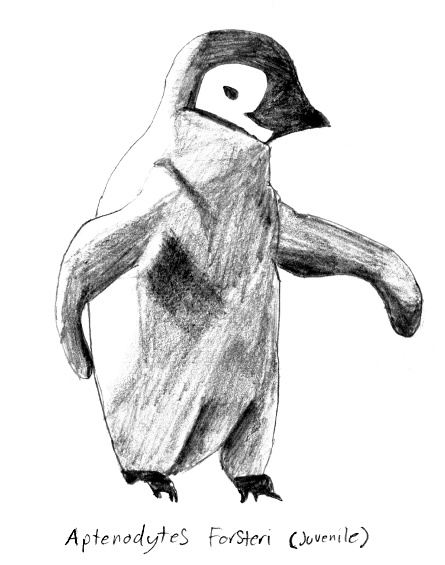

What you need instead is a way for the tasks to become easier the further behind you get. Either by cutting tasks, or by having alternate versions of those tasks that are less difficult. I've been trying that recently with my birdposts and it seems to be working better than trying to make up the time with regular posts. I've noticed that video games often do something similar by adjusting the difficulty if you're struggling.

Of course, even a badly aligned car or a negatively stable aircraft can be controlled by a skilled enough operator, where skilled enough sometimes means a computer. This doesn't really make negative stability any less bad, rather it just expands the scope of the system: the aircraft might be unstable, but the aircraft + flight control system is stable. Similarly, there might be unstable systems you deal with that are only stable because you are constantly supplying stabilising control inputs.

This is a dangerous state of affairs, doesn't scale well, and leads to cascading failures if you're the common stabilising factor in a lot of systems and you mess up. Better to have systems that remain stable without your constant vigilance. A well-trimmed aeroplane in smooth air will continue to fly straight and level with your hands off the controls entirely. Can you say the same about the other things in your life?

A year ago, I wrote High water mark, about the way that expectations tend to rise with results. Unchecked, this leaves you in a situation where eventually, inevitably, those expectations are too high to meet — kind of like a generalised Peter principle. I argued that the problem happens when the only influence on expectations is upwards, and I'd like to dig in to that idea of influence a little more.

I quite like the idea of loosely analysing motivation in terms of incentives. You don't need to understand every crevice of someone's psyche to analyse their behaviour, and you don't need to control every aspect of someone's behaviour to get them to do what you want. All you need are the broad strokes: what do they want, and does what you want help them get it? If that high-level connection between your goals and theirs is there, then the details aren't terribly important. And if it's not, no amount of micromanagement can really help you.

Influence is the generalisation of that idea. Much like you can broadly analyse someone's behaviour by the influence of their incentives, you can broadly analyse other systems by the influences that pull them in various directions. For example, in Control I wrote about the upward influences of personalisation and individual power on control, and in WONTFIX I wrote about the influence of not tolerating flaws on the way you make decisions. These are factors that don't dictate the behaviour of the system directly, but affect the way it changes over time.

In these cases and others, the answer often isn't to remove that influence; more control is a good thing, avoiding flaws is a good thing, and most influences are good (or the bad ones are pretty obvious and tend to be already dealt with). However, without any balancing influences, you get a system that only moves in one direction. An unchecked movement towards any influence is usually dangerous, because that leads to extreme behaviour and many situations are better served by nuance.

So I believe it's important to look out for situations with unbalanced influences. If there is something that pulls you towards working harder, is there something else that pulls you towards relaxation? One thing that makes you more stable and another that stops you getting stuck in a rut? What balances your influences to stop them from getting out of control?