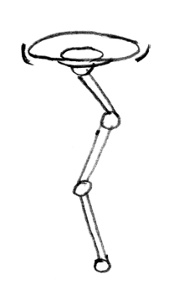

Points of articulation

It's much harder to control something that bends in two places than one. For example, balancing on the ground is pretty easy, but balancing on top of a skateboard is much harder. Even worse than that is when the two parts that balance are both trying to compensate for each other. If you're standing on someone's hands, your first instinct is to use your hips to balance, and their instinct is to move under you to balance, resulting in constant over-compensation and eventual pratfall.

In the context of short/long term, I think decisions also have this characteristic. You have one point of articulation in your planning and another in your execution. Making decisions in both places means your short-term and long-term interests both need to compensate for each other. You need to consider when planning that you may change your mind in the moment, and you need to consider in the moment that your plan may be relying on you to change your mind if necessary. Neither point of articulation can trust the other, so you end up second-guessing yourself.

So how do we fix this so we only have one point of articulation? One option would be to design our plans to have no leeway for change in the moment. That would require much more careful planning to account for situations you would otherwise be able to handle on the fly, and still leave you with a high risk of hitting something you didn't plan for. Another option would be not to plan, and just act in the moment. This gives you the benefit of maximum flexibility, but stops you from being able to react to large-scale problems or move consistently towards a big goal.

Both of these solutions are pretty unsatisfying, but maybe we can remove an assumption here: we don't have to operate at the scale of all decisions ever. You could plan some things up front, and leave some for the moment. And, combined with the observation that you can often break a decision down into smaller decisions, that gives a lot more flexibility. Instead of deciding the whole thing at once, you can split it into decide to make up front and decisions to make on the ground.

That sounds a little bit similar to the two-point-articulation situation we started with, but it has a couple of crucial differences. Firstly, the same decision doesn't get touched twice, so you could plan to go for a run sometime tomorrow and then decide to do it in the morning, but not plan to do it in the morning and then decide to do it in the afternoon. Secondly, as a consequence, you need to be very careful not to over-plan. If it doesn't matter whether you run in the morning or afternoon, you may as well leave it unspecified so you can decide at the time what works better.

Like balancing on someone's hands, that involves a certain degree of trust. In making your long-term plans, you need to be able to trust that your short-term actions will stay true to the plan. Conversely, your short-term decisions need to trust that the long-term plan is a good one. Defecting from the plan is a kind of relief valve; if you made a bad plan, you can back out when the badness becomes apparent. To stick to a single point of articulation means giving up that relief valve. So there's a certain degree of pressure in both directions to do the right thing.

That pressure is, in a sense, the real benefit of thinking in this way. You don't want to be second-guessing and compensating for your short-term decisions with your long-term ones or vice versa. Ideally each decision should be made by the most relevant process as best it can. The simpler that decision is, the easier it is, and the more likely to be correct.

The number of points of articulation in a decision is a major contributor to its complexity, so reducing that should lead to better plans, better implementation, and less pratfalls.