Strong statements, meaningful statements

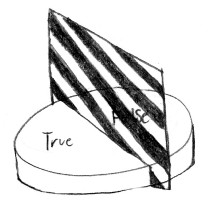

An idea I picked up somewhere, I think on Less Wrong somewhere but I can't find a reference now, is the idea that your theories should divide the space of concepts as evenly as possible. That is, there should be as many things that would confirm your theory as disprove it. You can picture there as being a big cake of things that might be true. To get the maximum information, you want to cut that cake in a way that lets you throw away the most of it each time you cut it. I like to call a statement like this meaningful.

A meaningful statement is something like "pigeons are blue" (or equivalently "pigeons aren't blue"), because it divides the space of pigeons into blue and not-blue. A meaningless statement would be something like "everything is made of energy". What would a not-made-of-energy-thing look like? If that's not a conceivable thing that could exist, then your concept space isn't being divided at all. You can imagine the cut in the cake going right down the side, missing the cake entirely. No matter what the outcome, it can't give you any new information!

Another way I like to think about statements is their strength. A strong statement is one with a clear test of its truth. An example of a strong statement is something like "I will go to the shops by 2pm", a weaker one would be "I will go to the shops today", weaker still would be "I will go to the shops sometime", and the weakest of all would be "I will try to go to the shops". You can see that, much like the meaningless statement, a weak statement also divides less of the concept space, but the reason is that it has a chunk of the concept space that it neither accepts nor rejects. The cake is still being cut, but with a big chunk left in the middle.

So if you put these two disciplines together you get strong, meaningful statements. These are statements that have a clear test of truth, and will divide a lot of things into either truth or falsehood when that test is applied. I recently learned an example of such a statement, which I'm told is related to Gendlin's Focusing technique. You say "my life is awesome and everything is going great". Although it's an emotional statement, it's strong because words like "awesome", "everything" and "great" are pretty definitive, and it's meaningful because there are a clear set of things in your life that could be either great or not great.

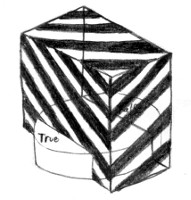

When most people make a statement like that, they feel uncomfortable, because it's not true that their life is awesome and everything is going great. So the next step is to keep adding exceptions to it: "everything is going great, except I wish I had a better job, and I wish I was in better shape, and I don't get enough holidays". Each additional statement is making additional cuts into the cake, effectively doing a binary search through the space to quickly converge on the exact set of things that are standing between you and an awesome life.

That's not to say I think every statement needs to be strong, or even meaningful, but I believe that strong and meaningful statements are the best way to quickly cut a path through concept-space. And if that turns out not to be the case, at least I'll have learned a lot by finding out.